Test for CRH-producing adenoma in Cushings Syndrome

Published:

Test for CRH producing adenoma in Cushings-Syndrome

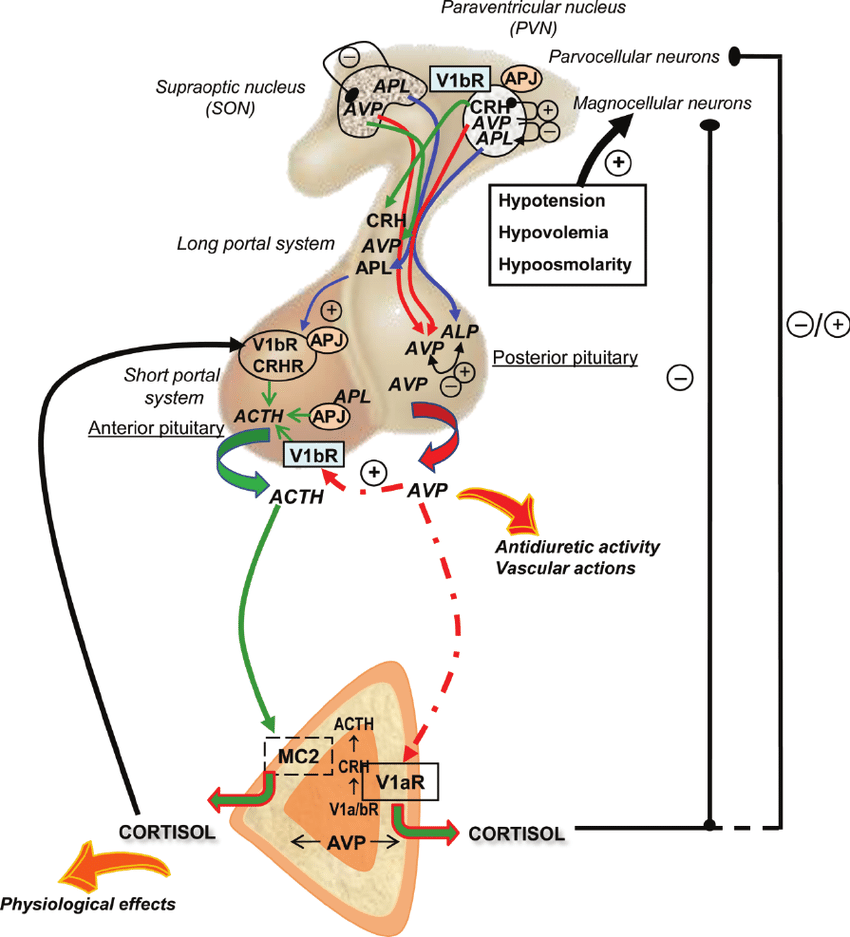

Cushing’s Syndrome is defined by features of glucocorticoid excess. Most commonly, these include: central obesity, rounded face, facial plethora, decreased libido. In humans, corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) is the hypothalamic releasing hormone that controls the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and thus glucocorticoid production. In rare instances, CRH-secreting tumours can arise and result in Cushing’s Syndrome.

Positive and negative feedback loops in the HPA axis with connection to the corticotroph adrenal axis (Gallo-Payet et al., 2008)

S&S of Cushing's Syndrome (Pivonello et al., 2008)

Workup for Cushing’s Syndrome

The standard workup for the differential diagnosis of Cushing’s Syndrome is shown below [2]. Note, however, that it does not explicitly mention CRH-secreting tumours due to their rarity. However, these are susceptible to the same tests that are effective in distinguishing Cushing’s disease (ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas) from ectopic sources of ACTH, such as neuroendocrine tumours (e.g. multiple endocrine neoplasias) and small cell lung cancer. Briefly, the workup proceeds as follows:

Tumours responsible for ectopic ACTH secretion

- Suspicion of Cushing’s Syndrome is established based on history, clinical features, and/or screening labs, which may include random cortisol.

- Hypercortisolism is established biochemically with two or more of the following (including repeats):

- Elevated 24-hour urine free cortisol levels

- Lack of suppression in the 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (aka “low-dose” DST)

- Elevated late-night (or midnight) salivary cortisol levels

- Plasma ACTH levels are measured, whereby elevated ACTH levels indicate “ACTH-dependent” Cushing’s Syndrome, and low ACTH levels indicated “ACTH-independent” Cushing’s Syndrome.

- ACTH excess and hypercortisolism require further workup to distinguish between pituitary and extra-pituitary sources of ACTH (Cushing’s disease and ectopic Cushing’s syndrome, respectively). This involves:

- Lack of supression in the high-dose DST suggests an ectopic source of ACTH. This can involve a single 8-mg dose (at midnight, with cortisol measured the next morning), or a 48-h course of 2-mg administered every 6 hours. Notably, the false positive rate is fairly high in both ectopic and pituitary disease, so Greenspan [3] claims that this test is no longer useful.

- Concomitant increases in ACTH and cortisol following CRH stimulation suggests a pituitary source of ACTH. However, the thresholds to distinguish ectopic and pituitary disease are quite high.

- High central-to-peripheral ratios of ACTH in inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS), taken before and after CRH stimulation, is the gold standard for diagnosing pituitary disease.

- Notably, the presence of other hormones and tumour markers commonly secreted by ectopic ACTH-secreting tumours are also helpful.

- Radiologic evaluation is helpful to guide diagnoses/treatment, e.g. MRI of the sella for Cushing’s disease or CTs of the chest and/or abdomen to look for ectopic tumours.

Workup for the differential diagnosis of Cushing's Syndrome (Pivonello et al., 2008)

Application to peripheral CRH-secreting tumours

The same tests can be applied to CRH-secreting tumours. For example:

- Initial biochemical screening will reveal high levels of ACTH and cortisol

- Due to their ectopic origin, neither low- nor high-dose DST will effectively suppress ACTH levels.

- Granted, there may be some suppression, as both CRH and dexamethasone act on corticotrophs.

- With CRH stimulation, ACTH levels may or may not increase above baseline.

- The case for a lack of elevation would be that corticotrophs are already fully stimulated.

- However, corticotrophs may also undergo hyperplasia, which may allow them to respond to CRH stimulation with elevated ACTH release.

- Indeed, Greenspan states that this can cause false positives in CRH stimulation testing [3].

- Imaging may reveal corticotroph hyperplasia, as mentioned above.

- With IPSS, an ectopic CRH-producing tumour produces a high central-to-peripheral ratio of ACTH, which is analogous to Cushing’s disease. Therefore, while a high IPS:P ratio strongly suggests CD, it does not exclude the possibility of a CRH-secreting tumour.

Summary table

Courtesy of ChatGPT (hence, caution):

| Test | Ectopic Cushing’s (ECS) | Cushing’s Disease (CD) | CRH-Secreting Ectopic Tumor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma ACTH | ↑↑ (markedly high, often >20 pmol/L or >100 pg/mL) | ↑ (moderately high, usually 5–20 pmol/L or 20–80 pg/mL) | ↑↑ (markedly high, often similar to ECS) |

| 24h Urine Free Cortisol (UFC) | ↑↑↑ (often >4× ULN) | ↑ (mild to moderate) | ↑ (mild to marked) |

| Midnight Salivary Cortisol | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Low-Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test (LDDST, 1 mg overnight or 2 mg over 48h) | No suppression | No suppression (or slight suppression) | No suppression |

| High-Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test (HDDST, 8 mg overnight or 2 mg q6h for 48h) | No suppression | Suppression >50% in most cases | Variable suppression (some cases suppress due to pituitary-like response) |

| CRH Stimulation Test (ACTH & Cortisol response to CRH injection) | No response (flat ACTH & cortisol) | Exaggerated ACTH & cortisol rise | Exaggerated ACTH & cortisol rise |

| Inferior Petrosal Sinus Sampling (IPSS, basal ACTH & CRH-stimulated ACTH lateralization) | No central-to-peripheral ACTH gradient (<2 at baseline, <3 after CRH) | Central-to-peripheral ACTH gradient ≥2 (baseline) or ≥3 (after CRH) | Central-to-peripheral gradient (like Cushing’s disease) |

| Basic Imaging (Pituitary MRI, Chest/Abdomen CT/MRI) | Often normal pituitary; ectopic source (lung, pancreas, thymus) seen on CT/MRI | Pituitary microadenoma in ~50% | Corticotroph hyperplasia, ectopic mass |

References

- Gallo-Payet, N., Roussy, J. F., Chagnon, F., Roberge, C., & Lesur, O. (2008). Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis multiple and organ dysfunction syndrome in critical illness: A special focus on arginine-vasopressin and apelin. Journal of Organ Dysfunction, 4(4), 216–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/17471060802339711

- Pivonello R, De Martino MC, De Leo M, Lombardi G, Colao A. Cushing’s Syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008 Mar;37(1):135-49, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.10.010. PMID: 18226734.

- Gardner DG, Shoback D. eds. Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology, 10e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017. Accessed March 12, 2025. https://accessbiomedicalscience.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2178§ionid=166246461