Thoughts on blood pressure and renin release

Published:

Blood pressure

I found the handout from one of today’s lectures (attached) useful in clarifying the interplay and effects of the various BP regulation mechanisms. In particular,

- arterial blood pressure is collectively regulated by VSMCs (vascular smooth muscle cells) in small arteries and arterioles, whose resistances are both regulated by central mechanisms, e.g. NE, ang II

- in addition to central control, specific vascular beds have additional, independent regulatory mechanisms, including myogenic and paracrine/autocrine mechanisms

- as mentioned in lecture, the myogenic mechanism is initiated by stretch-sensitive (TRP) channels, which depolarize the VSMCs and cause calcium-dependent contraction via actin-myosin interactions

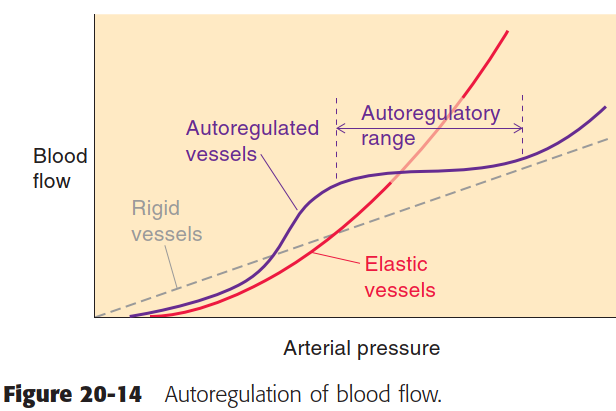

- “autoregulation” refers to the ability of VSMCs in specific tissues to contract or relax to maintain perfusion (flow rates) in those areas within a narrow range in the face of large changes in systemic arterial pressure.

Boron 14-2 Autoregulation of blood flow

Renin release

The release of renin is controlled by three pathways, all of which sense effective circulating fluid volume (ECFV):

- renin release is inversely related renal perfusion pressure (RPP; baroreceptor reflex), e.g. ↓ BP ∝ ↑ renin

- increased NaCl delivery to the macula densa inhibits renin release

- sympathetic stimulation (NE) of JG cells increases renin release via β1-ARs

The way these pathways interact is complex. Consider:

- Ang II acts within the CNS to increase sympathetic drive (e.g. NE release), thirst, and ADH release.

- NE increases systemic vascular tone and arterial pressure through α-ARs on VSMCs

Hence, increased sympathetic tone can stimulate renin release and vasoconstriction.

- Although the JG cells themselves may not produce contractile force, constriction of the afferent arteriole would tend to decrease renal blood flow and eventually inhibit renin release via the baroreceptor reflex.

- If so, it would seem that sympathetic control of renin release is a futile cycle, stimulating renin release on the one hand while indirectly inhibiting renin secretion through vasoconstriction on the other.

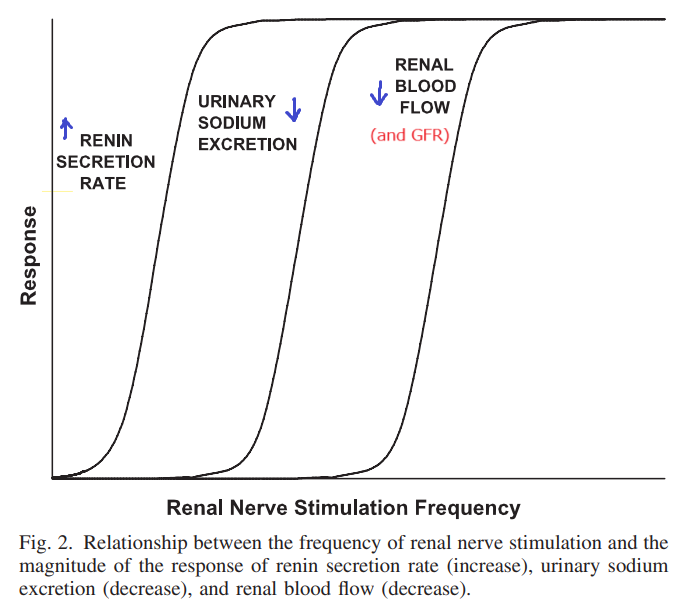

This ‘paradox’ has been explained by distinguishing between two regimes of renal sympathetic nervous activity (RSNA). In lecture, we learned that this effect is dependent on the ‘strength’ of sympathetic stimulation: ‘mild’ RSNA stimulates renin release and renal tubular sodium reabsorption without affecting RBF and GFR, whereas ‘strong’ RSNA results in vasoconstriction. [2](https://sci-hub.ru/10.1152/ajpregu.00258.2005)

Relationship between frequency of renal nerve stimulation and the magnitutde of response of renin secretion, sodium excretion, and renal blood flow

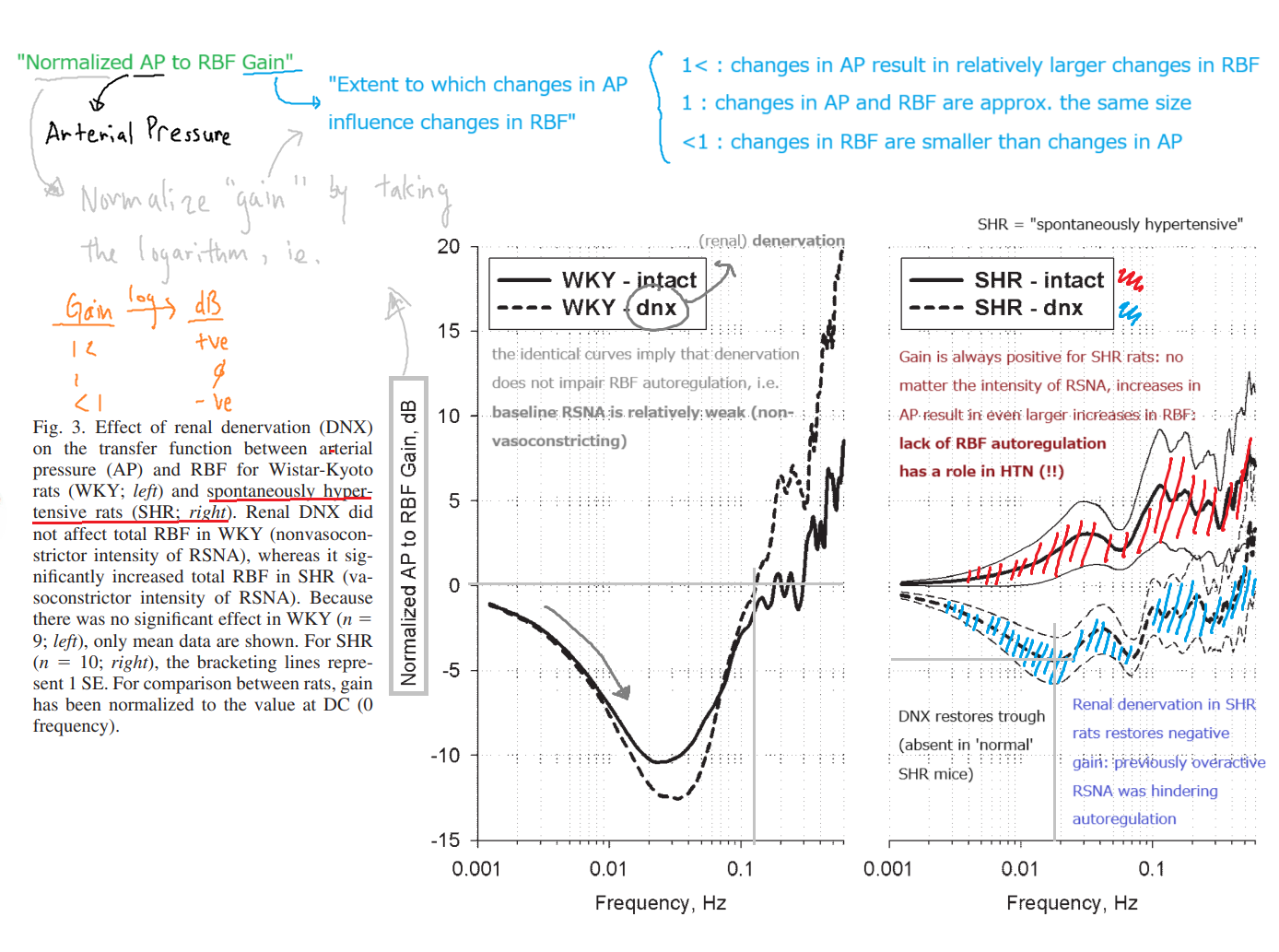

If only high, but not low, frequency RSNA causes vasoconstriction, we can predict that selective ablation of high, but not low, frequency RSNA should impair RBF autoregulation by increasing the BP threshold that triggers autoregulation. That is,

- Autoregulation, through the myogenic or TGF mechanisms, is the kidney’s intrinsic ability to keep RBF relatively constant despite changes in arterial pressure (AP).

- Both the myogenic and TGF mechanisms respond to increased AP by inducing vasoconstriction of the preglomerular arterioles.

- However, high RSNA puts these vessels into a contracted state, which limits the ability of RBF autoregulation to counteract sudden increases in AP.

- Consequently, larger increases in AP are required to initiate autoregulation, resulting in a narrowed autoregulatory range (see previous section).

This distinction between vasoconstrictor and non-vasoconstrictor RSNA has been elegantly demonstrated via denervation experiments in rats. In animal studies, renal denervation has been consistently shown to ameliorate hypertension (e.g. [2], [6]), whereas a controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension in humans did not show significant reduction in BP. This may be due to incomplete denervation or ‘re-programming’ of sympathetic stimulation, as the trial relied on pharmacological depletion of NE for denervation, and the extent of denervation was not confirmed, e.g. by histology.

Effect of renal denervation on the transfer function between AP and RBF

References

- Boron, 2e

- Physiology in perspective: The Wisdom of the Body. Neural control of the kidney. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 289(3), R633–R641, 10.1152/ajpregu.00258.2005

- Astrocytes Contribute to Angiotensin II Stimulation of Hypothalamic Neuronal Activity and Sympathetic Outflow, Hypertension (ahajournals.org)

- Integration of Hypernatremia and Angiotensin II by the Organum Vasculosum of the Lamina Terminalis Regulates Thirst, Journal of Neuroscience (jneurosci.org)

- Structural basis for reduced glomerular filtration capacity in nephrotic humans - PubMed (nih.gov)

- Long-term renal sympathetic denervation ameliorates renal fibrosis and delays the onset of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats - PMC (nih.gov)

- A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension - PubMed