MS2.2 FFM Case Review 1

Published:

Today, I had my first FFM (focused family medicine) session and I thought there were some cases that I wanted to review and learn more about, so I am recording my notes of these cases here.

- 1. Infant with infectious diarrhea

- 2. AL amyloidosis with new-onset atrial fibrillation

- 3. Painful knee after fall

- References

1. Infant with infectious diarrhea

Case Summary

9 month old female infant presents with 3 days of cough, rhinorrhea, and diarrhea with 10 bowel movements/day. Coughing occasionally produces green sputum. The cough is worse when supine. Diarrhea is watery and dark. She has had stomach pain, which improved with Infant Tylenol (1 ml every 6-8 hours as needed). There has been no fever and vomiting. The mother is concerned because she heard wheezing sounds last night.

She was delivered a few weeks pre-term by C-section following an uncomplicated pregnancy. She has been otherwise healthy. She has been feeding well with formula and recent introduction fo solids. She lives with her mother and father, a dog and 2 cats. Both mother and father have had similar symptoms for the past couple weeks. There is no travel history. She and both parents are up to date on vaccinations. She is lactose intolerant.

Vitals are normal for her age. On exam, she appears well and energetic, with no abnormal findings.

Problem representation

9 month old female infant presents with acute cough, rhinorrhea, and watery diarrhea, with no abnormal exam findings.

CDM grid

| Rank | Diagnosis | Supporting | Refuting |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acute viral upper respiratory infection | Short duration (3 days); cough and rhinorrhea; no fever; similar symptoms in both parents; normal vitals and exam; green sputum can occur with viral illness due to neutrophils and post-nasal drainage | No significant lower respiratory signs on exam (no wheeze, crackles, retractions); cough productive description may be caregiver interpretation |

| 2 | Acute viral gastroenteritis (e.g., norovirus, adenovirus) | Watery, dark diarrhea with high frequency (10/day); mild abdominal pain; no blood or mucus; no fever or vomiting; sick contacts in household; well-appearing infant | No signs of dehydration; continues to feed well; diarrhea only 3 days in duration |

| 3 | Viral bronchiolitis (e.g., RSV) | Age <1 year; rhinorrhea and cough; caregiver-reported wheezing; worse when supine | Normal respiratory exam (no wheeze, crackles, or increased work of breathing); normal vitals; energetic and feeding well |

| 4 | Post-nasal drip–related cough | Common in infants with viral URIs; cough worse when supine; green sputum likely swallowed nasal secretions; nocturnal “wheezing” may represent upper airway sounds | Does not explain diarrhea; diagnosis of exclusion; no direct visualization of post-nasal drainage |

| Critical 1 | Pneumonia | Cough; caregiver concern for wheeze | No fever; no tachypnea; no hypoxia; normal lung exam; well appearance |

| Critical 2 | Dehydration secondary to gastroenteritis | High stool frequency | Normal skin turgor; moist mucous membranes; normal capillary refill; normal fontanelle; feeding well; energetic |

| Critical 3 | Sepsis | Young age | Afebrile; normal vitals; well-appearing; no lethargy, irritability, or poor feeding |

Notes

- Assess for signs of dehydration: urine output (no. of wet diapers - difficult to assess here due to diarrhea), tears, mucous membranes, and capillary refill

- Monitor for progression: work of breathing, wheezing, new fever

- Indications for infectious diarrhea panel:

- Mild-moderate symptoms ≥ 7 days

- Severe symptoms:

- ≥ 10 stools/day

- bloody stools

- fever ≥ 38.5c

- pain

- Severe immunocompromise, e.g. cancer, transplant, or untreated HIV

- Presence of blood or mucus in stool suggests bacterial pathogens

- Viral testing only if symptoms worsen

- No routine labs or imaging unless changes in clinical status

Management of infectious diarrhea [1]

- Modify or discontinue antimicrobial therapy once a clinically plausible organism is identified.

- Continue human milk feeding in infants and children throughout the diarrheal episode.

- Resume age-appropriate usual diet during or immediately after completion of rehydration.

Symptomatic Therapies

Antimotility Agents

- Not recommended in children <18 years with acute diarrhea (strong, moderate).

Loperamide:

- May be used in immunocompetent adults with acute watery diarrhea (weak, moderate).

Avoid at any age in:

- Suspected or confirmed inflammatory diarrhea

- Diarrhea with fever

- Risk of toxic megacolon (strong, low)

Antiemetics

Ondansetron may be used to facilitate oral rehydration in:

- Children >4 years

- Adolescents with vomiting from acute gastroenteritis (weak, moderate)

Empiric Antimicrobial Therapy

Acute Watery Diarrhea

- Not recommended in most patients without recent international travel (strong, low).

Exceptions:

- Immunocompromised individuals

- Young infants who are ill-appearing

Avoid empiric therapy in:

- Persistent watery diarrhea ≥14 days (strong, low)

Asymptomatic contacts:

- Do not offer empiric or preventive therapy

Bloody Diarrhea

In immunocompetent children and adults, empiric therapy while awaiting results is not recommended (strong, low), except:

- Infants <3 months with suspected bacterial etiology

Ill immunocompetent patients with:

- Documented fever

- Abdominal pain

- Bloody diarrhea

- Features of bacillary dysentery (frequent scant bloody stools, fever, cramps, tenesmus), presumptively due to Shigella

Recent international travelers with:

- Temperature ≥38.5°C

- Signs of sepsis (weak, low)

Asymptomatic contacts of patients with bloody diarrhea:

- Do not offer empiric therapy

- Advise infection prevention and control measures

Recommended Empiric Antimicrobials (When Indicated)

Adults:

- Fluoroquinolone (eg, ciprofloxacin) or

- Azithromycin

- Choice depends on local susceptibility patterns and travel history (strong, moderate)

Children:

Third-generation cephalosporin:

- Infants <3 months

- Children with neurologic involvement

Azithromycin as an alternative based on local resistance and travel history (strong, moderate)

Rehydration therapies

| Degree of Dehydration | Rehydration Therapy | Replacement of Losses During Maintenance |

|---|---|---|

| Mild to moderate dehydration | Infants and children: ORS 50–100 mL/kg over 3–4 hours Adolescents and adults (≥30 kg): ORS 2–4 L | Infants and children: • <10 kg: 60–120 mL ORS per diarrheal stool or vomiting episode (up to ~500 mL/day) • >10 kg: 120–240 mL ORS per diarrheal stool or vomiting episode (up to ~1 L/day) Adolescents and adults: • Ad libitum, up to ~2 L/day Replace losses as above as long as diarrhea or vomiting continues |

| Severe dehydration | Infants: Malnourished infants may benefit from smaller, frequent boluses of 10 mL/kg due to limited ability to increase cardiac output with large volumes Children, adolescents, and adults: IV isotonic crystalloid boluses per current resuscitation guidelines (up to 20 mL/kg) until pulse, perfusion, and mental status normalize; adjust electrolytes and administer dextrose based on labs | Infants and children: • <10 kg: 60–120 mL ORS per diarrheal stool or vomiting episode (up to ~500 mL/day) • >10 kg: 120–240 mL ORS per diarrheal stool or vomiting episode (up to ~1 L/day) Adolescents and adults: • Ad libitum, up to ~2 L/day Replace losses as above as long as diarrhea or vomiting continues. If unable to drink, administer via nasogastric tube or IV 5% dextrose in 0.25 normal saline with 20 mEq/L potassium chloride |

2. AL amyloidosis with new-onset atrial fibrillation

Case Summary

A 50–70-year-old man with AL amyloidosis, nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypertension, and mild coronary artery disease presents with 1 week of productive cough and mild chest pain. Symptoms began 3 days after his monthly subcutaneous daratumumab injection.

The cough produces green sputum without hemoptysis. He denies progression of symptoms, dyspnea on exertion, or resting shortness of breath. He reports mild (2–3/10), diffuse anterior chest pain that is non-radiating and not exacerbated by exertion, stress, or position.

He denies lightheadedness, dizziness, syncope, palpitations, abnormal heart rate or rhythm awareness, fever, nausea, vomiting, or gastrointestinal association with meals. There is no history of trauma. He does not smoke, drink alcohol, or use recreational drugs.

His home medication includes ramipril, which he has not taken since yesterday.

Physical exam Vitals are stable. On exam, he is well-appearing and shows no signs of respiratory distress. Soft inspiratory crackles are heard at the bilateral lung bases. Heart rhythm is irregularly irregular. There are no murmurs. The rest of the cardiac and respiratory exam was normal.

Investigations ECG shows atrial fibrillation, with erratic baseline and ventricular rate of 95 bpm. Deep negative deflections are seen in V1-V2. In V2 only, QRS complexes are followed by upsloping ST elevation with tall T waves.

Chest X-ray (AP and lateral views):

- Airway: midline trachea

- Breathing: lungs symmetrically expanded; lung fields clear with normal vascular markings tapering peripherally

- Circulation: cardiac silhouette normal in size; no mediastinal shift or widening; normal mediastinal contours and hila.

- Diaphragm: costophrenic angles sharp bilaterally; gastric bubble present

- Other: No fractures or skeletal abnormalities

Problem representation

50–70-year-old man with AL amyloidosis, nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypertension, and mild coronary artery disease presents with a subacute productive cough and mild, non-exertional anterior chest pain following recent daratumumab administration, found to have atrial fibrillation with anterior ECG abnormalities but a normal chest X-ray and stable vital signs.

CDM grid

| Diagnosis | Supporting Factors | Refuting / Lowering-Likelihood Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Acute bronchitis | • Subacute onset of productive cough with green sputum • Absence of systemic toxicity • Normal chest X-ray (no consolidation) • Inspiratory crackles can be present • Immunosuppression from daratumumab ↑ infection risk • Clinical diagnosis per AAFP in absence of pneumonia or chronic lung disease | • Green sputum is nonspecific • Immunocompromised state raises concern for deeper infection |

| Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) | • Immunocompromised status (daratumumab) • Radiographic findings may lag early in disease • Mild or atypical presentations described in impaired immunity | • No fever • No dyspnea • Normal chest X-ray • No systemic toxicity |

| Lower respiratory tract infection related to daratumumab | • Daratumumab associated with ↑ risk of respiratory infections • Timing relative to recent administration • Cough and sputum production | • No severe systemic features • Normal imaging • Symptoms consistent with uncomplicated bronchitis |

| Atrial fibrillation with RVR–related chest discomfort | • Irregularly irregular rhythm • ECG consistent with AF • Chest discomfort often mild, non-exertional in AF • Known association per ACC/AHA/ESC | • Chest pain not clearly temporally linked to tachyarrhythmia • Presence of respiratory symptoms suggests alternative cause |

| GERD / esophageal spasm | • Atypical, non-exertional chest pain • Lack of objective cardiac or pulmonary findings • GI causes account for ~20% of outpatient chest pain | • Does not explain productive cough or sputum • No clear reflux-associated symptoms reported |

| Pulmonary embolism (PE) (must not miss) | • Increased thrombotic risk (amyloidosis, nephrotic syndrome) • Can present with cough and mild chest pain | • No dyspnea • No hemoptysis • Normal chest imaging • Overall low clinical suspicion; requires risk stratification (Wells/Geneva, D-dimer) |

| Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (must not miss) | • Chest pain in patient with known CAD and AF • Mild or atypical presentations possible | • Non-exertional, mild pain • No ischemic ECG changes reported • No associated autonomic symptoms (e.g., diaphoresis) |

| Early infective endocarditis (must not miss) | • Immunocompromised state • Underlying cardiac disease (AF) • Can present subtly in immunosuppressed patients | • Afebrile • Normal cardiac exam • No embolic or systemic signs |

Management of amyloidosis

In AL amyloidosis, standard heart failure and arrhythmia algorithms often do not apply — management must be individualized, cautious, and coordinated across specialties.

1. Disease-Modifying Therapy

- Cornerstone of treatment: Chemotherapy targeting the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia

- Goal:

- Halt amyloid light-chain production

- Improve organ function and survival, particularly cardiac outcomes

- Early initiation is critical and requires close hematology collaboration

Common Regimens

| Agent | Role / Notes |

|---|---|

| Bortezomib | Proteasome inhibitor; backbone of many regimens |

| Melphalan | Alkylating agent; often combined with steroids |

| Dexamethasone | Enhances plasma cell suppression |

| Daratumumab | Anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody; FDA-approved for AL amyloidosis in combination regimens |

2. Heart Failure Management

- Heart failure in AL amyloidosis is typically restrictive

- Management focuses on symptom control, not traditional HFrEF remodeling

Volume Management (Mainstay)

| Strategy | Key Points |

|---|---|

| Loop diuretics | Use lowest effective dose to avoid hypotension |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | Adjunctive volume control |

| Sodium restriction | Recommended in all patients |

Medications to Avoid or Use with Extreme Caution

| Drug Class | Reason |

|---|---|

| Beta-blockers | Poor tolerance; may reduce cardiac output |

| ACE inhibitors / ARBs | High risk of hypotension |

| Calcium channel blockers | Negative inotropy; can worsen symptoms |

- These agents often worsen hemodynamics due to fixed stroke volume

- If used, require very careful titration

Renal Considerations

- Close monitoring of renal function is essential due to:

- Nephrotic-range proteinuria

- Direct renal amyloid deposition

- Diuretic-induced hypovolemia

3. Arrhythmia and Atrial Fibrillation Management

Anticoagulation

- Indicated for all patients with atrial fibrillation

- Independent of CHA₂DS₂-VASc score

- Rationale: markedly increased risk of:

- Intracardiac thrombus

- Systemic embolization

| Option | Notes |

|---|---|

| DOACs | Acceptable |

| Warfarin | Acceptable |

| Bleeding risk | Must be carefully assessed |

Rhythm and Rate Control

| Strategy | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Rhythm control | Amiodarone or dofetilide preferred |

| Avoid | Agents with negative inotropic effects |

| Rate control | Low-dose beta-blockers only if tolerated |

Cardioversion

- Transesophageal echocardiography required before cardioversion

- Necessary regardless of anticoagulation duration to exclude left atrial appendage thrombus

4. Device Therapy and Advanced Interventions

| Intervention | Role / Limitations |

|---|---|

| ICD | Limited benefit; poor outcomes; ↑ infection & bleeding risk |

| LVAD | Generally unfavorable risk–benefit profile |

| Pacemaker | Consider for recurrent syncope or advanced conduction disease |

| Heart transplantation | Reserved for select patients; reassessed during chemotherapy |

- Device decisions must consider:

- Active chemotherapy

- Infection risk

- Limited survival benefit in advanced disease

5. Multidisciplinary and Supportive Care

- Optimal care requires a multidisciplinary team, including:

- Cardiology

- Hematology

- Nephrology

- Other specialties as needed

Supportive Measures

- Salt restriction

- Careful diuretic titration

- Management of:

- Autonomic dysfunction

- Bleeding diathesis

- Renal impairment

- Other comorbidities

Goal: Symptom relief, organ preservation, and complication prevention

Common infections in older adults with immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis and proteinuria

The most common infections seen in older adults with immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis and nephrotic-range proteinuria are bacterial respiratory tract infections (such as pneumonia and bronchitis), urinary tract infections, and skin/soft tissue infections. This increased susceptibility is due to several factors: AL amyloidosis is associated with functional hyposplenism, which impairs clearance of encapsulated bacteria (notably Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae); nephrotic-range proteinuria leads to urinary loss of immunoglobulins and complement proteins, further compromising humoral immunity; and older age itself is a risk factor for infection.

Patients with nephrotic syndrome, including those with AL amyloidosis, are also at increased risk for peritonitis and sepsis from gram-negative organisms due to impaired immune defenses. [2] Opportunistic infections may occur, especially in those receiving immunosuppressive therapy for underlying plasma cell dyscrasia. [1], [2] Viral infections (such as influenza and herpes zoster) are also more frequent in this population. [1]

Notes on amyloidosis [2]

The presence of an unexplained multisystem illness, fatigue, or organ dysfunction that does not fit common disease patterns should prompt evaluation for amyloidosis.

Pathogenesis

- Systemic amyloidosis is defined by abnormal folding of a normally soluble precursor protein, leading to insoluble fibril deposition.

- In AL (light-chain) amyloidosis, abnormal folding occurs due to:

- Proteolytic events or

- Amino acid sequence changes that render immunoglobulin light chains thermodynamically and kinetically unstable

- Misfolded light chains self-aggregate and interact with:

- Glycosaminoglycans

- Serum amyloid P protein

- These interactions promote amyloid fibril formation, stabilize tissue deposits, disrupt normal tissue architecture, and ultimately cause organ dysfunction.

Immunoglobulin Characteristics

- Lambda light chains: 75–80%

- Kappa light chains: 20–25%

- Rare forms:

- AH amyloidosis (heavy chain)

- AH/AL amyloidosis (heavy + light chains)

Genetic Features

- t(11;14) translocation:

- Involves IgH locus and cyclin D1

- Present in ~50% of AL amyloidosis cases

- Hyperdiploidy:

- Common in multiple myeloma

- Seen in ~10% of AL amyloidosis cases

- Somatic mutations in IGLV genes:

- Encode the light-chain variable region

- Reduce protein stability and facilitate fibril formation

Risk Factors

- Exact risk factors remain unclear

- Common associations:

- Monoclonal gammopathy

- Multiple myeloma

- MGUS:

- Relative risk: 8.8

- ~1% incidence of AL amyloidosis in long-term follow-up

- Multiple myeloma:

- AL amyloidosis in 10–15%

- 38% have Congo red–positive deposits

- Additional associations:

- Rising monoclonal free light chains precede diagnosis by >4 years

- Possible association with Agent Orange exposure (limited evidence)

- N-glycosylation of kappa light chains predicts earlier AL diagnosis in MGUS

Epidemiology

- Data limited due to lack of comprehensive population registries

- Incidence increases with age

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Incidence (1950–1989, Olmsted County) | 8.9 / million person-years |

| Incidence (1970–1989) | 10.5 / million person-years |

| Incidence (1990–2015) | 12.0 / million person-years |

| Global crude incidence | ~10.4 / million person-years |

| Estimated global cases (past 20 yrs) | ~74,000 |

| Estimated incidence (2018) | 10 / million population |

| Estimated 20-yr prevalence | 51 / million population |

| U.S. prevalence (2007 → 2015) | 15.5 → 40.5 / million |

| U.S. incidence | Stable (9.7–14.0 / million person-years) |

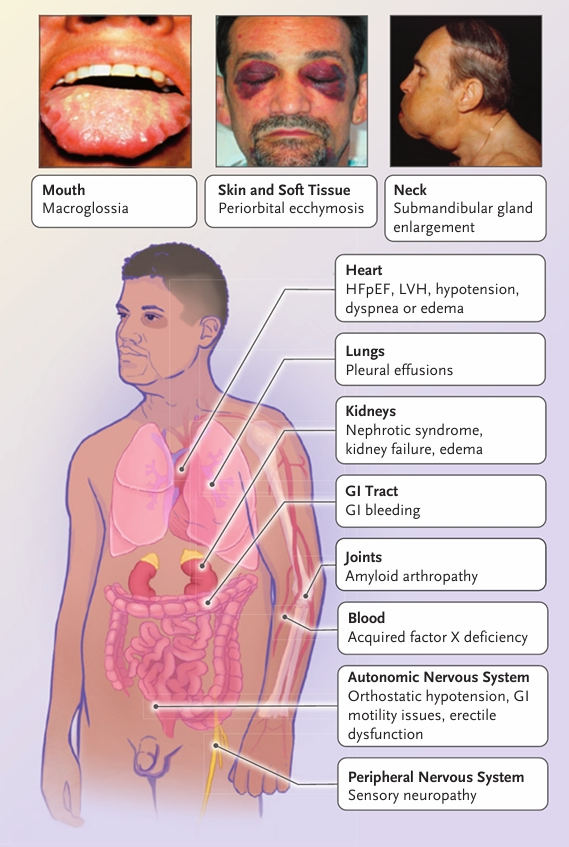

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation of AL amyloidosis [[2]](#ref-2)

- Typically rapidly progressive

- Diagnosis often delayed due to:

- Nonspecific early symptoms

- Low clinician awareness

- General

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Renal (60–70%)

- Nephrotic-range proteinuria

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Secondary hyperlipidemia

- Edema

- Renal failure may occur without proteinuria due to interstitial or vascular deposition

- Cardiac (70–80%) — Leading cause of death

- Early:

- Low voltage ECG

- Concentric ventricular thickening on echocardiography

- Diastolic dysfunction

- Other features:

- Poor atrial contractility (even in sinus rhythm)

- High risk of atrial thrombi and embolism

- Elevated troponin and/or NT-proBNP

- Bradyarrhythmias often precede terminal decompensation

- Early:

- Neurological

- Small-fiber neuropathy

- Autonomic dysfunction:

- GI dysmotility

- Early satiety

- Dry eyes/mouth

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Neurogenic bladder

- GI

- Macroglossia: 10–20%

- Liver:

- Hepatomegaly

- Cholestasis

- Hyperbilirubinemia (often terminal)

- Spleen: Functional hyposplenism (not splenomegaly)

- Hematologic / Cutaneous:

- Easy bruising

- Factor X deficiency

- Ecchymoses

- Nail dystrophy

- Alopecia

- Musculoskeletal: Amyloid arthropathy

3. Painful knee after fall

I think this is an interesting case because, as I mention below, I felt the patient had difficulty understanding what I was saying, even though I was speaking in Cantonese. Granted, she had hearing aids and I might have been speaking too quietly for her to hear. Further, she seemed to be able to understand my English-speaking preceptor and follow most of his commands without trouble during the physical exam. Nonetheless, OpenEvidence seems to believe that this case involves a central neurological process: link to OpenEvidence chat.

Case Summary

62-year-old woman presents with 1 month of progressive left knee pain and left leg weakness. Two weeks ago, she fell while descending stairs and landed directly on her left patella. She attributes the onset of her knee pain to this fall.

She is accompanied by her brother, who lives with her. He reports observing progressive difficulty with walking that began several years ago. He notes that her knee pain began worsening approximately 1 month ago, which was prior to the fall that occurred 2 weeks ago.

The patient has no chronic medical conditions. She takes no regular medications.

The patient communicates primarily using short phrases and gestures. Her brother provides most of the historical information during the interview. She appears to occasionally not understand or hear when addressed in Cantonese, which is her primary language, by either myself or her brother.

Physical exam [3]

- General Appearance: The patient appears well and is not in acute distress. Her vital signs are stable. There is prominent exotropia of the left eye. She has hearing aids in both ears.

- Gait Analysis: The patient walks independently without assistive devices. She walks with a left-sided limp. The stance phase is prolonged on the left leg. During the swing phase, the left leg appears straight and stiff. The right leg demonstrates wide, stiff-legged circumduction during swing phase. Step length is reduced on the left side. There is no dragging of the feet. Turning is smooth.

- Inspection: There are no skin discolorations, rashes, or bruising of the lower extremities. Hair and nail distribution are normal. There is no visible swelling. Muscle bulk appears normal and symmetric bilaterally. The knees appear slightly enlarged bilaterally but show normal alignment both frontally and laterally. There is no genu varum or valgus deformity.

- Palpation: Skin temperature is normal. There are no swellings or deformities detected. Maximal tenderness is present at the joint line of the tibiofemoral joint. Moderate tenderness is present on palpation over the patella, patellar tendon, and anteromedial crest of the tibia. There is no tenderness over the muscles, superior pole of the patella, fibular head, pes anserine bursa, Gerdy’s tubercle, or popliteal fossa.

- Range of Motion: Passive range of motion is normal and symmetric bilaterally. Active range of motion is slightly decreased on the left leg due to pain.

- Special Tests: There is no laxity of the medial collateral ligament or lateral collateral ligament. The anterior drawer test is negative. The posterior drawer test is negative. The patellar ballottement test is negative. The fluid wave test is negative. No Baker’s cyst is palpated.

- Vascular Examination: The popliteal, posterior tibialis, and dorsalis pedis pulses are palpable and symmetric bilaterally.

- Neurological Examination: Power is 4/5 on both legs, except for 3/5 left knee flexion and extension. Reflexes not assessed.

Problem Representation

62 year old woman with chronic gait difficulty presents with acute-on-chronic left-sided knee pain and weakness in flexion/extension after a fall from standing height, suggesting chronic degenerative joint disease +/- central neurological changes.

CDM table

Most Likely Diagnoses

| Diagnosis | Supporting Features | Refuting Features |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical Myelopathy | Progressive bilateral leg weakness (4/5 power); spastic gait pattern with stiff-legged circumduction; prolonged stance phase; chronic progressive course over years; age 62 (typical for cervical spondylosis); altered gait mechanics could explain secondary knee pain | Communication difficulties not typically prominent in isolated myelopathy; no documented upper extremity symptoms; reflexes and upper motor neuron signs not assessed |

| Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus | Progressive gait disturbance with wide-based, stiff gait; cognitive/communication difficulties; chronic progressive course (~1 year by patient report, years per collateral history); classic triad presentation | Urinary incontinence not mentioned; turning described as smooth (typically impaired in NPH); no documented cognitive testing to confirm dementia |

| Neurodegenerative Disorder with Motor and Cognitive Features | Progressive bilateral leg weakness; communication difficulties with language comprehension impairment; spastic gait with upper motor neuron features; bilateral hearing loss; exotropia (may suggest neurological disease); chronic progressive course | Relatively preserved function (independent ambulation); no family history documented; no tremor, rigidity, or other parkinsonian features noted |

| Corticobasal Syndrome or Atypical Parkinsonian Disorder | Progressive asymmetric motor symptoms; communication/language difficulties; exotropia; spastic features; chronic progressive course | No documented apraxia, alien limb phenomenon, dystonia, or cortical sensory loss; no tremor or rigidity noted; turning smooth (typically impaired in parkinsonism) |

Critical Diagnoses Not to Miss

| Diagnosis | Supporting Features | Refuting Features |

|---|---|---|

| Compressive Spinal Lesion or Structural CNS Pathology | Progressive bilateral leg weakness; spastic gait pattern; chronic progressive course; requires urgent treatment to prevent permanent disability | No acute neurological deterioration; no documented sensory level; no bowel/bladder symptoms mentioned |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Motor Neuron Disease | Progressive bilateral leg weakness; potential upper motor neuron features (spastic gait); chronic progressive course | No documented lower motor neuron signs (fasciculations, atrophy, hyporeflexia); no bulbar symptoms; muscle bulk appears normal and symmetric; communication difficulties may suggest cognitive involvement atypical for pure ALS |

| Frontotemporal Dementia-Motor Neuron Disease Spectrum | Progressive communication difficulties with language comprehension issues; motor weakness and gait abnormalities; bilateral involvement | No documented bulbar symptoms (dysphagia, dysarthria); no behavioral changes mentioned; no fasciculations noted; relatively preserved function |

| Stroke/Subcortical Vascular Disease | Communication difficulties; bilateral leg weakness; gait abnormalities; bilateral hearing loss (vascular risk) | Gradual progressive onset over years (not stepwise); no acute events documented; smooth turning suggests preserved basal ganglia function |

Less Likely Diagnoses

| Diagnosis | Supporting Features | Refuting Features |

|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis with Incidental/Secondary Findings | Age 62; bilateral knee enlargement; maximal tenderness at tibiofemoral joint line; moderate tenderness over patella and patellar tendon; knee pain | Does not explain bilateral leg weakness, spastic gait pattern, or communication difficulties; normal muscle bulk argues against disuse atrophy from chronic pain |

Key Additional History and Follow-up Tests:

Detailed neurological history: Onset and progression of weakness, presence of fasciculations, muscle cramps, dysphagia, dysarthria, changes in handwriting or fine motor skills, bowel/bladder dysfunction, sensory symptoms, family history of neurodegenerative disease

Cognitive and language assessment: Formal neuropsychological testing to characterize the nature of communication difficulties (aphasia vs. dysarthria vs. hearing impairment), executive function, memory domains

MRI of cervical spine and brain: Essential to evaluate for cervical myelopathy, structural lesions, hydrocephalus, patterns of atrophy suggesting specific neurodegenerative disorders, and vascular disease

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies: To assess for lower motor neuron involvement, distinguish between myelopathy and motor neuron disease, and evaluate for peripheral neuropathy

Formal audiometry: To distinguish hearing loss from primary language/cognitive impairment

Reflexes assessment: Hyperreflexia, clonus, Babinski sign, Hoffmann’s sign to confirm upper motor neuron involvement

Gait analysis and functional testing: Timed up and go test, assessment of turning, balance testing to characterize gait disorder

Laboratory studies: Vitamin B12, thyroid function, inflammatory markers, creatine kinase to exclude metabolic or inflammatory causes of weakness

Lumbar puncture with CSF analysis: If NPH suspected, can assess opening pressure and consider large-volume tap test for diagnostic and prognostic purposes

Knee imaging (X-ray or MRI): To evaluate the extent of osteoarthritis and exclude other causes of knee pain, though this is secondary to establishing the neurological diagnosis