SGLT2 inhibitor induced eDKA and Exercise induced hypoglycemia

Published:

Table of Contents

- SGLT2 inhibition-induced euglycemic DKA

- Exercised-induced hypoglycemia in the absence of exogenous insulin or medications

SGLT2 inhibition-induced euglycemic DKA

This is a rare complication of SGLT2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) use. The mechanisms are not well understood, but I describe one that is personally appealing:

- SGLT2i increases glycosuria, lowering blood glucose

- Low blood glucose triggers ↓ insulin and ↑ glucagon

- Relative insulin deficiency leads to ↑ hepatic glucose production (offset by glycosuria and lipolysis)

- Increased β-oxidation produces excess acetyl-CoA beyond oxidative capacity

- Excess acetyl-CoA converts to ketones via ketogenesis

- When ketogenesis exceeds metabolic clearance, ketoacidosis develops despite normal glucose (“euglycemic” DKA)

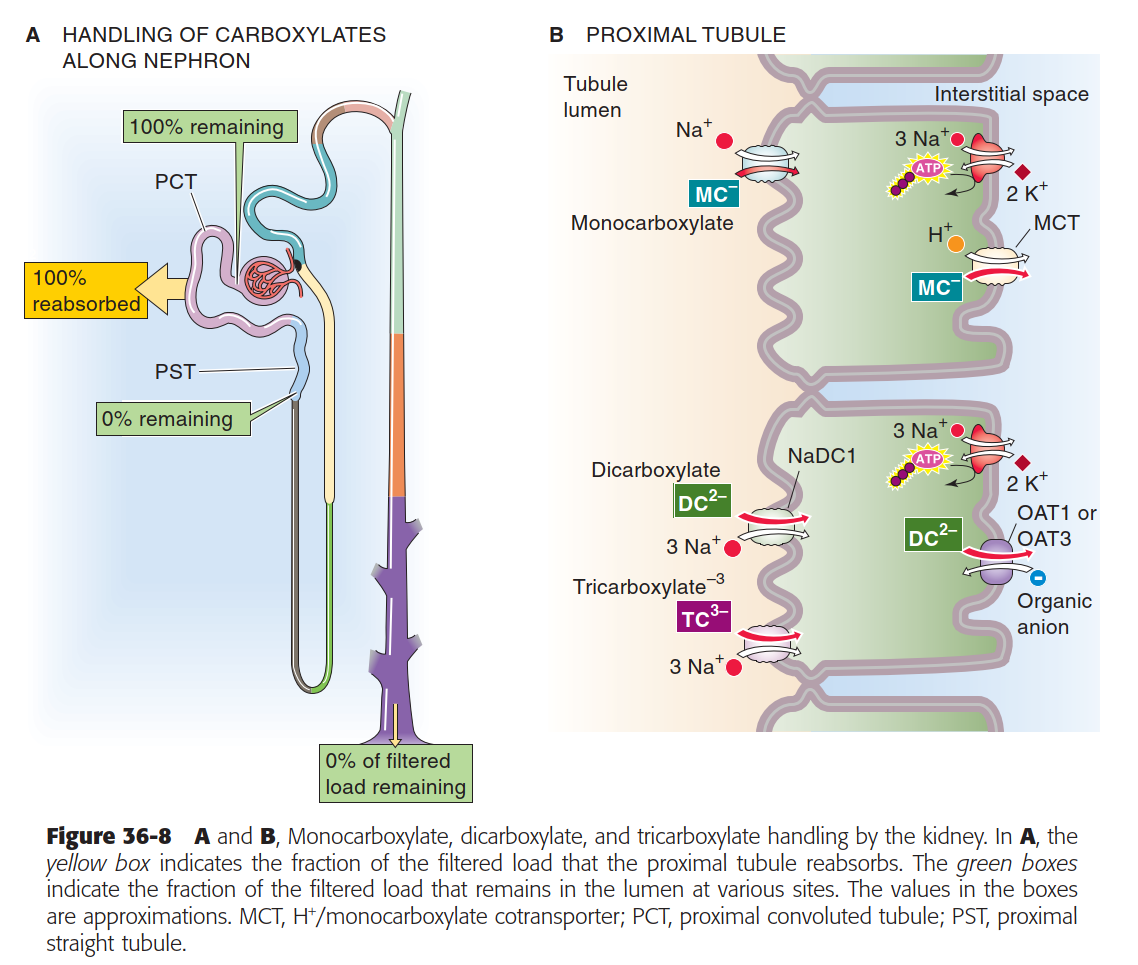

- Moreover, note that renal handling of mono-, di-, and tri-carboxylic acids is primarily mediated by secondary Na$^+$-dependent co-transporters (see figure below). Thus, because SGLT2 inhibitors reduce Na$^+$ reabsorption, there is a greater drive for reabsorption of ketone bodies (dicarboxylates) through these transporters. This can exacerbate and/or accelerate the pathogenesis of eDKA.

Like with hyperglycemic DKA, management of eDKA should begin with fluid resuscitation to replenish volume. Insulin infusion should follow to stop ketosis, and electrolytes should be monitored to avoid hypokalemia, supplementing with K$^+$ as necessary. The major difference in clinical management between euglycemic and hyperglycemic DKA is that dextrose should be added to the initial IV solution to avoid hypoglycemia.

Boron 36-8 Monocarboxylate, dicarboxylate, and tricarboxylate handling by the kidney

Exercised-induced hypoglycemia in the absence of exogenous insulin or medications

Exercise alters glucose metabolism through the upregulation of GLUT4 transporters in skeletal muscle and processes that, collectively:

- enhance peripheral insulin sensitivity and

- reduce circulating plasma glucose.

Under normal physiological conditions, the body responds to increased energetic demand by decreasing insulin secretion while increasing glucagon production. In diabetes, however, these regulatory mechanisms become dysfunctional:

- Normal feedback loops fail to appropriately modulate insulin and glucagon levels, and

- When exogenous insulin or insulin secretagogues are present, they operate independently of these physiological controls.

This disruption creates a significant risk of exercise-induced acute hypoglycemia. But what might explain exercise-induced hypoglycemia in the absence of exogenous insulin or insulin secretagogues? For example, consider pre-diabetic individuals or those with undiagnosed diabetes.

Several mechanisms may contribute:

- First, β-cell dysfunction may result in continued insulin secretion despite exercise-induced increases in peripheral glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity.

- Similarly, an impaired glucagon response can limit or delay compensatory glucose production.

- Depending on exercise intensity, there is a risk of delayed hypoglycemia if post-exercise nutritional intake fails to adequately replenish muscle and liver glycogen stores.

Consider also the role of catecholamines. While they typically inhibit insulin secretion and promote hepatic glucose production, lipolysis, and ketogenesis, their effects in diabetic conditions can vary:

- In the presence of low pre-exercise insulin levels, intense exercise-induced catecholamine release may precipitate ketoacidosis.

- Conversely, the catabolic effects of catecholamines during high-intensity exercise might help prevent acute hypoglycemia. However, this protective effect likely does not eliminate the need for post-exercise carbohydrate replacement, i.e. the risk of delayed hypoglycemia persists.